2016 Passage to Hawaii – Days 0-9

November 21st, 2016 | by Marilyn | Published in Ship's Log

We finally did it! We made the “Left Turn” that sailors in Puget Sound talk about over beers with fellow sailors, and while sitting at home poring over old Pilot Charts and Jimmy Cornell’s World Cruising Routes. That “Left Turn” means we sailed to Neah Bay at the west end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and turned southward to the shockingly blue waters of the open ocean and to warmer climes. Last summer’s sail to Glacier Bay was a milestone for us – we had reached a goal we had dreamed of for years, and had not been disappointed by the spectacular adventure. It was amazing, but it was also cold sitting in a fiberglass boat floating in water just a few degrees above freezing. Up there, we knew we were ready for warmer waters.

The tipping point came in January 2016, when we were offered a mooring at Hilo’s Wailoa Basin, so we decided to bring our boat to the Big Island of Hawaii. It typically takes 25 days for a cruising boat of Rainshadow’s size to do this passage from Neah Bay, Washington to Hilo, Hawaii, so it’s a commitment to life at sea.

The planning went well. Our neighbor Eric jumped at the chance to be crew. We ordered supplies online and had them shipped to friends in Washington state. The boxes were piled high in their garage, awaiting our return to our (now former) home port on North Kitsap peninsula. Van arrived at the boat in late May, then Marilyn arrived June 1st. We took delivery on our new Neil Pryde working jib and mizzen. We worked like fiends to get ready. Eric arrived on June 6th.

On June 7th, the three of us slipped away into the early morning fog of Hood Canal. As we motored north, we encountered our first ‘event’. We nearly had a fire in the engine room, as described here on our svRainshadow.Tumblr.com site.

Undaunted, we continued on, spending a week in Bellingham working on the boat. For a shakedown, we spent a few days buddy-boat cruising in the San Juan Islands with Mary and Jim on Dan Ran. We were even joined for an evening by Kate and Carl aboard S/V Mom (http://www.sv-mom.com/). Then we sailed south through Cattle Pass, and turned west.

In Port Angeles, we stocked up on more fresh food and made final modifications to Rainshadow in preparation for the voyage. Putting a solid bar in front of the stove, and putting a wide strap in the galley were two of the more important updates. You don’t want to be thrown against a hot stove underway, and you could lean against the strap in heavy seas while cooking.

Leaving Port Angeles early in the morning, Eric took the helm, and almost immediately the winds and waves turned nasty. Steep chop outside Ediz Hook sent Rainshadow plunging up and down, and as we struggled to maintain control, the pump handle in the head went airborne and lodged itself behind the door, effectively locking it shut. You can read how we freed it here on our svRainshadow.Tumblr.com site.

Once we arrived at Neah Bay on Tuesday June 21st, we waited for 3 full days for some suitable offshore winds to develop. Finally, on Saturday June 25th at 1330 PDT, we set off from the Neah Bay fuel dock and didn’t touch land again for almost 29 days until we made landfall at Hilo Bay on Saturday July 23rd about 0800PDT (0500 HST). But there is much more to the story about our first passage than that brisk statement.

Before we begin telling the full story, we want to express a heart-felt THANK YOU to Peter, our friend who was our land-based weather router during our entire passage. Peter is an experienced ocean race navigator and veteran of many Pacific Cup crossings. Daily, he texted us through our very nifty Delorme InReach device to guide us to our preferred wind conditions, and around the series of storms to the south. The passage would have been much harder without Peter’s help.

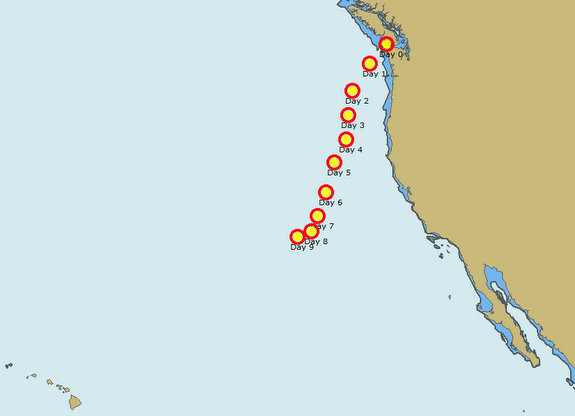

Now, back to the story of our passage. (My apologies to our land-lubber readers that much of what follows uses sailing jargon.) The first part of our journey was along the U.S. West Coast, down to the Horse Latitudes (about 30° N). We had a steep learning curve during these first days at sea.

Day 0: We motored out of Neah Bay and headed west. By the time we reached Tatoosh Island, we had enough westerly headwind to light air sail. After getting away from the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the wind strengthened and veered to the NW. Thankfully, the rest the passage we had a following wind.

It was on this first day that we learned our solent stay interferes with the headboard on the new working jib, so we cannot use the furler with the solent stay in place. That’s bad because it reduces our flexibility when using double headsails, making it harder to reef the sails quickly.

At dusk on Day 0, we double-reefed the main out of caution for what the night might bring. Later as the wind built, we experienced severe weather helm. In the dark of night, we decided to drop the main and sail with the jib alone until daylight. In the days to come, we learned that to properly balance the sail plan when flying the smaller area working jib on a reach, we needed to reef the main and tune it carefully.

On this first night, we also had problems with the control lines for the Monitor wind vane (our mechanical self-steering gear). Eventually the Monitor control lines failed, and each of us in turn spent hours hand steering until daylight came and we could see well enough to re-tie the control lines. Hand steering became all too common during the first days at sea because we did not have sufficient experience with the Monitor to know how to best set it up for the varying conditions. Hand steering becomes tiring, especially at night.

By midnight, we had traveled 50 nm from Neah Bay (distances are from midnight to midnight each day, and are based on GPS tracks).

On Day 1 at sea, we were about 100 miles off the central WA coast in 18-20 knot winds and rough seas. Sadly, we had our third ‘event’ when the head clogged (AKA the toilet stopped working). This had never happened before. We had hopes it would fix itself in time, so left it to sit for a while to let things “soften up”. We sailed 141 nm this day, making good progress.

By Day 2, we were about 170 miles off the central Oregon coast in 15-18 knot winds and 3’ swells. We started using double-head sails to sail dead-down-wind (DDW). We made great southerly progress. Unfortunately, the head was still clogged, so there was nothing for it but to take apart the pump. Van and Eric bravely tackled the pump as the boat pitched in the following seas. Eventually, they learned that the clog was caused by a tough wad of toilet paper stuck in the exit valve of the pump. Calcium salt build-up in the valves made the problem worse. We set strict rules about nothing down the toilet unless it’s been through your body first, and we had no further problems.

Near nightfall, Van prudently decided double-headsails were too risky overnight because (remember) we cannot furl the working jib if the solent stay is up. By this time, we were also learning that twilight seemed to bring stronger and more erratic winds so sail plan changes became the norm every evening. This erratic overnight winds also helped explain why the Monitor did fairly well during daylight, but each night it was troublesome.

Gales were developing off the Oregon and Northern California coasts, so we needed to get further offshore. We chose a starboard broad reach with a poled-out jib to make further westerly progress overnight. But the wind dropped in the night when we made too much westing and approached the doldrums of the Pacific High. This resulted in another middle of the night sail plan change to drop the pole and gybe onto a port tack.

The sail change went fine, but Marilyn had taken a 4 hour night watch just prior to this sail plan change and was completely worn out. We set a more strict 2 hour night watch schedule and kept to that for the rest of the trip. A two hour watch was much easier, even if it meant you only got four hours off at a time. And with generous sharing and swapping of shifts, we managed to work around each others tiredness and needs for rest.

The lighter winds reduced our distance this day to 98 nm.

On Day 3, we were about 180 miles off the coast of southern Oregon in 15-18 knot winds and sunny skies. This is the first day we saw jellyfish with sails! These unique jellyfish are called Velella, and you can read about them here: http://jellywatch.org/velella We saw thousands of Velella over the coming days. Distance traveled Day 3 = 157 nm.

Day 4 started with setting up double headsails again at 0600, and we generally had an easy morning in warmer condition with 15-18 knot winds, though the seas were still confused. We were about 200 miles off the northern California coast. About 1600, we were astonished by our first boarding wave dumping tens of gallons of seawater into cockpit, leaving water sloshing a few inches deep. This had never happened to us before in 6 years of cruising! We had some surprised laughter, and were happy the water quickly disappeared through the cockpit scuppers. Little did we know that boarding waves would be all too common for the rest of the passage because of the frequent steep sided waves, often coming from multiple directions. But we learned how to tie down the cockpit canvas so that we never took on that much water again, though we often got some.

That evening, at about 2030, the wind increased to 25-30 knots, so we decided to change from double headsails to working jib and reefed main. Van is extremely good on deck, but this was a difficult sail plan change due to the rough sea conditions. We each demonstrated our ability to keep cool under pressure.

Distance traveled Day 4 = 158 nm.

Early on Day 5 , we had problems with Monitor control lines. As they stretched, we unintentionally ended up sailing FAST on a beam reach at a large angle to the direction we wanted to go. At 0300, Van and Marilyn worked together to get things under control. Both of us recognized that fatigue was affecting our ability to think.

Later, the Monitor control lines chafed through at the helm, so the electrical Neco autopilot came on to relieve the exhausted crew. Beside requiring a lot of power to run, the problem with the Neco is it steers a course relative to the compass, while the Monitor wind steers a course relative to the wind direction.

There is a big difference between these two behaviors. With the Neco in erratic winds, you need to constantly adjust the course setpoint to stay at the proper sail trim. And if the wind changes direction too much (for example during a gust), you can accidently gybe. With the Monitor behavior, you may not sail the preferred course, but you don’t have to trim the sails nor tweak the setpoint as much. Both have their advantages, but at sea, a well-adjusted wind vane is generally preferable because it is less work for the crew.

During Day 5, we were in 20-25 knot winds about 250 miles off Cape Mendocino, an area known for crappy conditions. Peter sent a message saying he was worried about developing Hurricane Agatha, currently off the coast of Mexico. We were not going to be in it – but we were at risk of it robbing us of wind and stranding us in unpleasant seas. We were faced with the reality of how serious a game we were playing when we committed to spend this long at sea. Marilyn was exhausted and spent much of the day sleeping. Again the night involved considerable hand-steering because we couldn’t get the Monitor set up right for the rough conditions. We travelled 175 nm that day, much of that due to strong helpful currents.

Day 6, we were about 400 miles west of San Francisco in 18-22 knot winds under sunny skies. Air temperature was 74 F, but the sea temperature is still only 61 F. Eric actually put on shorts and a t-shirt. But no one was very happy – the seas were rough and unpleasant. While we had dodged the gale force winds off the coast, we were dealing with their waves coming in at an angle to the normal waves and swells.

On our electronic charting software, OpenCPN, we saw several distant AIS targets that were SF and LA shipping traffic. Eric actually saw the lights of a cargo boat on his night watch – our first visual sighting of another vessel since Day 0. Traveled 147 nm for the day, 953 nm since Neah Bay.

A typical view from the cockpit during our passage

Day 7, we were about 500 miles off the central CA coast with 15-20 knot winds in confused seas with 6’ swells. The wind indicator fell off the mast and dangled by a small wire onto the SSB radio triatic antenna, shorting it out so we could not send SSB messages. Fortunately we could still receive and so were able to continue to download the weatherfax. Not having a wind indicator on the mast was another nasty twist of events – in our enclosed cockpit we are sheltered from the wind and rain, but that means you need visual indicators to know where the wind was coming from. The masthead indicator was the most important one. At least we still had the anemometer to give us wind direction, shown on a gauge in the cockpit. We hoped it wouldn’t fail, too. It had in past years, but we’d been able to climb the mast and fix it at the dockside.

Traveled 160 nm, again helpful current pushing us along.

In the wee morning hours of Day 8, there was only a light wind that was not enough for the rough sea state. Without enough wind, the waves make the boat rock wildly and the sails slat hard shaking the whole rig. It’s nearly impossible to sleep through such noise, so Marilyn begged to heave-to for awhile so we could all sleep. (Heaving-to means setting the sails so the boat takes care of itself but you make little progress.) After 3 1/2 hours of sleep, we got the boat underway again at 0730. Marilyn was still exhausted and spent midday sleeping. Van and Eric set up the Neco autopilot and gave up on the Monitor. Later we ended up motoring for some time in the afternoon to charge the batteries. We found a bolt on deck that came out of the boom near the gooseneck. Van put it back. It was not nice that the boat was having failures.

By evening, we were about 600 miles west of Santa Barbara and the wind was around 14-16 knots. We feared the Monitor couldn’t work in these lighter winds, but miraculously we got it set up perfectly. This is when we finally realized that in the early days when the wind was so strong, we had been using too large an area wind vane paddle and that’s why the Monitor was doing so poorly. We should have been using a smaller paddle! Happily the Monitor worked ALL NIGHT and no one had to hand steer. Even when the wind kicked up to 20 knots during the night, all went well with the Monitor. It was nice to have a night with no drama. We only traveled 135 nm that day, thanks to the light winds in the morning.

Day 9 was the 4th of July. Under guidance from Peter, we had rounded the SE corner of the Pacific high (where the doldrums are), and were able to turn west. We were about 700 miles from Santa Barbara, and solidly in the Horse Latitudes where the wind speed was light – only 10-15 knots from NE. But the sea state was better and for the first time we could relax.

In the morning, the wind indicator arrow that was stuck on the triatic antenna fell to the deck and bounced into the water. In the afternoon, we enjoyed flying the mizzen staysail until the winds became too strong for this light air sail. Then we doddled along under genoa alone. We saw a cargo ship called the Horizon Enterprise. The person on watch hailed us on the VHF radio and we had a nice chat about the conditions, Hawaii (his home) and life at sea. It was nice. He asked why were moving so slowly. Later the weatherfax showed Hurricane Blas had developed south of us. We decided it was stupid to doddle and set sail on a starboard broad reach. 136 nm for the day.

You can just see on the horizon the cargo boat we spoke to on 4th of July, with a Hawaiian named Freedom on watch.

You can read about the following days adventures in the next post.